Tuesday, December 28, 2010

Susan Campbell's Non-Fiction Class

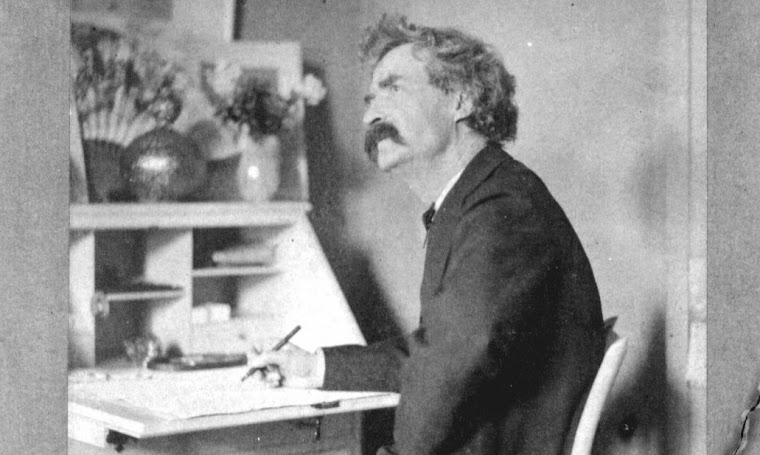

They pledged to continue the conversation online -- that extraordinary collection of writers who met for six sessions in the Mark Twain House & Museum classroom during November and December 2010. Susan Campbell, the feisty Hartford Courant columnist whose memoir of religion and feminism, Dating Jesus, has won praise and prizes, provided wild in-class writing exercises ("Write down what Elizabeth Edwards would be telling John from Heaven"), led far-ranging and passionate discussions. The participants, in turn, wrote heartfelt pieces, ranging from intimate memoirs to biography to strong expository prose. Selections from the works of these students and their teacher (who found the experience profoundly engaging and educating herself) will be appearing on this blog soon. -- Steve Courtney

Friday, September 3, 2010

Lary Bloom wins Lifetime Achievement Award from Connecticut Center for the Book

Lary Bloom, the longtime editor, writer and teacher, has been designated this year's winner of the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Connecticut Center for the Book. Lary, of course, taught our memoir class this past spring along with Suzanne Levine, and suggested the idea of Writing at the Mark Twain House.

At the same ceremony, Susan Campbell, teacher of our fall Creative Non-Fiction Class, won the Connecticut Book Award for her memoir of fundamentalism and feminism, Dating Jesus.

Congratulations to Lary and Susan!

...and to Suzanne Levine, whose book of poetry Haberdasher's Daughter recently came out (read about it here).

...and to Bessy Reyna, whose Memoirs of the Unfaithful Lover has been out for a while now! Read about it here. To bring things full circle, Bessy, who has long provided a strong and principled voice, along with a powerful lyric style, to her poetry, was last year's Lifetime Achievement winner. -- Steve Courtney

At the same ceremony, Susan Campbell, teacher of our fall Creative Non-Fiction Class, won the Connecticut Book Award for her memoir of fundamentalism and feminism, Dating Jesus.

Congratulations to Lary and Susan!

...and to Suzanne Levine, whose book of poetry Haberdasher's Daughter recently came out (read about it here).

...and to Bessy Reyna, whose Memoirs of the Unfaithful Lover has been out for a while now! Read about it here. To bring things full circle, Bessy, who has long provided a strong and principled voice, along with a powerful lyric style, to her poetry, was last year's Lifetime Achievement winner. -- Steve Courtney

Wednesday, August 4, 2010

"Play Ball" by Beverly LeConche

This post and those following are by students in Lary Bloom's and Suzanne Levine's Memoir class, Spring 2010.

The day I was born the Red Sox won a double header against the Washington Senators, 5-4 and 10-4.

About 10 years later my father started taking the family to Yankee baseball games in New York. I remember him driving through the heavy traffic and swearing at the crazy city drivers. Many times we visited Yankee Stadium to cheer on the Bronx Bombers. That was the old Yankee Stadium, the real Yankee Stadium. I’ve never been to the new one. Around the time I started high school, we stopped going to ballgames. I guess maybe the New York City traffic got to be too much for my father, or maybe he just got bored with the Yankees.

My mother tells me that, as a child, I would insist on sitting in front of the TV with my father to watch baseball. She says I asked a million questions: Why are they getting a new pitcher? What’s a balk? Why is the batter out if he didn’t swing at the ball? My mother never cared about baseball. She went to the games with us, but didn’t pay attention. She’s 89 now and still doesn’t get it.

My younger brother was born a Yankees fan. He had 8 X 10 Yankee publicity photos on his bedroom wall and made anyone entering his room memorize all the players’ names: Cletus Boyer, Mickey Mantle, Whitey Ford, Bobby Richardson, Roger Maris, Elston Howard, Yogi Berra. If I went into his room, I had to recite their names. He collected baseball cards, too. Now he wonders what happened to his baseball card collection. He figures my mother, a clean freak, threw them out along with his Beatles cards. Fifty years later, my brother still roots for the Yankees.

My father and I, on the other hand, finally saw the light and became Red Sox fans in 1967, the year of the Red Sox Impossible Dream, when they reached the World Series for the first time in 21 years. It was impossible not to be a Sox fan after that. A few years later, I thought I was a Minnesota Twins fan for a while, because I was in love with Harmon Killebrew. I even named my first car Harmon. It was a 1970 Ford Maverick. But that affair didn’t last long. I soon switched back to the Sox.

My family spent several weeks every summer at Chapman Beach in Westbrook. We always had a portable radio with us on the beach, tuned to the Yankee games. I can still hear Mel Allen (and later Phil Rizzuto) yelling “Holy cow!” when the Yanks scored a run. Those were my favorite days. There was nothing to do on those long summer days but swim, sit on the beach, and listen to baseball.

In the Wethersfield house my family lived in for 30 years, if you looked closely, you could see where one of the spokes on the staircase had been repaired. My brother cracked it in 1960, angry that the Pirates beat the Yankees in the World Series. He still gets angry when his team loses.

In 1969, the Mets finally went from being the laughing stock of baseball to being in the World Series. That was back when they used to play day games. I was a student at UCONN and used to rush back from my last class each day to watch the Series. Some students didn’t bother going to class at all. They stayed in the dorm in front of the TV. The Mets won the Series. Everyone cheered including me. In college I met a fellow Red Sox fan. She was from Rhode Island and didn’t mind driving in Boston traffic, so she drove Harmon to Fenway Park. We saw about five or six games a year for those four years we were at UConn. Then we graduated. She got married, and moved to Virginia.

I joined VISTA and was sent to Arizona. That was 1972, the year of the baseball players’ strike. I know, because I had tickets to a game I never got to see. I mailed the tickets from Arizona to a friend in Connecticut, but I don’t think he ever used them. It doesn’t matter, though; back then it only cost $6.50 for box seats along the first base line.

I missed the Sox for the nine years I lived in Arizona, but at least I could watch spring training. The San Francisco Giants trained in my town, Casa Grande, and a hotel in town had and still has a swimming pool in the shape of a baseball bat and a wading pool in the shape of a ball. I did get to see the 1975 World Series on TV, and the famous scene with Carlton Fisk waving his arms at the ball to stay fair. That was the greatest game ever, but the Sox lost the Series. My brother sent me a sympathy card which I still have. I reciprocated by sending him one the following year when the Yankees lost to Cincinnati.

I own my own home now and have a craft room that is decorated with Red Sox banners, memorabilia, and photos, and each year at Christmas, one of my trees is decorated totally with Red Sox ornaments.

My niece got married two years ago. The day she got married the Sox were playing the Yankees. My brother, the father of the bride, grabbed the microphone and announced to all present, how happy he was on this joyous occasion, and by the way, the Yankees were whipping the Red Sox 10-3. My grand-nephew, Gabriel, was born last August 31. For Christmas he received a Yankees hat from my brother and a Red Sox layette and bib from me, both of us trying to make sure Gabe got started off on the right foot.

My father lived to be ninety years old. The night before he died, the Sox played the Yankees at Fenway. We called an ambulance to take my father to Hartford Hospital because he couldn’t breathe. As he was being wheeled into the emergency room, just hours before he died, he asked, “Are the Sox winning?”

The day I was born the Red Sox won a double header against the Washington Senators, 5-4 and 10-4.

About 10 years later my father started taking the family to Yankee baseball games in New York. I remember him driving through the heavy traffic and swearing at the crazy city drivers. Many times we visited Yankee Stadium to cheer on the Bronx Bombers. That was the old Yankee Stadium, the real Yankee Stadium. I’ve never been to the new one. Around the time I started high school, we stopped going to ballgames. I guess maybe the New York City traffic got to be too much for my father, or maybe he just got bored with the Yankees.

My mother tells me that, as a child, I would insist on sitting in front of the TV with my father to watch baseball. She says I asked a million questions: Why are they getting a new pitcher? What’s a balk? Why is the batter out if he didn’t swing at the ball? My mother never cared about baseball. She went to the games with us, but didn’t pay attention. She’s 89 now and still doesn’t get it.

My younger brother was born a Yankees fan. He had 8 X 10 Yankee publicity photos on his bedroom wall and made anyone entering his room memorize all the players’ names: Cletus Boyer, Mickey Mantle, Whitey Ford, Bobby Richardson, Roger Maris, Elston Howard, Yogi Berra. If I went into his room, I had to recite their names. He collected baseball cards, too. Now he wonders what happened to his baseball card collection. He figures my mother, a clean freak, threw them out along with his Beatles cards. Fifty years later, my brother still roots for the Yankees.

My father and I, on the other hand, finally saw the light and became Red Sox fans in 1967, the year of the Red Sox Impossible Dream, when they reached the World Series for the first time in 21 years. It was impossible not to be a Sox fan after that. A few years later, I thought I was a Minnesota Twins fan for a while, because I was in love with Harmon Killebrew. I even named my first car Harmon. It was a 1970 Ford Maverick. But that affair didn’t last long. I soon switched back to the Sox.

My family spent several weeks every summer at Chapman Beach in Westbrook. We always had a portable radio with us on the beach, tuned to the Yankee games. I can still hear Mel Allen (and later Phil Rizzuto) yelling “Holy cow!” when the Yanks scored a run. Those were my favorite days. There was nothing to do on those long summer days but swim, sit on the beach, and listen to baseball.

In the Wethersfield house my family lived in for 30 years, if you looked closely, you could see where one of the spokes on the staircase had been repaired. My brother cracked it in 1960, angry that the Pirates beat the Yankees in the World Series. He still gets angry when his team loses.

In 1969, the Mets finally went from being the laughing stock of baseball to being in the World Series. That was back when they used to play day games. I was a student at UCONN and used to rush back from my last class each day to watch the Series. Some students didn’t bother going to class at all. They stayed in the dorm in front of the TV. The Mets won the Series. Everyone cheered including me. In college I met a fellow Red Sox fan. She was from Rhode Island and didn’t mind driving in Boston traffic, so she drove Harmon to Fenway Park. We saw about five or six games a year for those four years we were at UConn. Then we graduated. She got married, and moved to Virginia.

I joined VISTA and was sent to Arizona. That was 1972, the year of the baseball players’ strike. I know, because I had tickets to a game I never got to see. I mailed the tickets from Arizona to a friend in Connecticut, but I don’t think he ever used them. It doesn’t matter, though; back then it only cost $6.50 for box seats along the first base line.

I missed the Sox for the nine years I lived in Arizona, but at least I could watch spring training. The San Francisco Giants trained in my town, Casa Grande, and a hotel in town had and still has a swimming pool in the shape of a baseball bat and a wading pool in the shape of a ball. I did get to see the 1975 World Series on TV, and the famous scene with Carlton Fisk waving his arms at the ball to stay fair. That was the greatest game ever, but the Sox lost the Series. My brother sent me a sympathy card which I still have. I reciprocated by sending him one the following year when the Yankees lost to Cincinnati.

I own my own home now and have a craft room that is decorated with Red Sox banners, memorabilia, and photos, and each year at Christmas, one of my trees is decorated totally with Red Sox ornaments.

My niece got married two years ago. The day she got married the Sox were playing the Yankees. My brother, the father of the bride, grabbed the microphone and announced to all present, how happy he was on this joyous occasion, and by the way, the Yankees were whipping the Red Sox 10-3. My grand-nephew, Gabriel, was born last August 31. For Christmas he received a Yankees hat from my brother and a Red Sox layette and bib from me, both of us trying to make sure Gabe got started off on the right foot.

My father lived to be ninety years old. The night before he died, the Sox played the Yankees at Fenway. We called an ambulance to take my father to Hartford Hospital because he couldn’t breathe. As he was being wheeled into the emergency room, just hours before he died, he asked, “Are the Sox winning?”

Thursday, July 8, 2010

"Unexpected Gifts" by Charlene O'Sullivan Distefano

“I wasn't there that morning when my Father passed away. I didn't get to tell him all the things I had to say. I think I caught his spirit later that same year...I just wish I could have told him in the living years.” – from the song “The Living Years” by Mike Rutherford and B.A. Robertson

I sat in my childhood home in New Britain, Connecticut, in Dad's 1960s-decorated kitchen, counting his weekly pills into morning and evening doses, and reflected that I was now taking care of Charles “Chappy” O'Sullivan, who had taken care of me his entire life. We had just returned from making pre-paid funeral arrangements for both him and Mom, whose debilitating stroke had left her in a nursing home, never to recover or return home. Dad would be waked from the Irish funeral home in town, Mom from the Swedish.

My year-long layoff from Aetna from dried-up project funding would gift me with time to enjoy Dad's company as never before.

Dad and I reviewed the contents of their safe deposit box, including details of how my birth parents gifted me to my parents, and Mom's letter to the adoption agency presciently recounting what a wonderful father Dad would make.

I took Dad to lunches, and once ordered a pricey wine just to “get his goat.” Sure enough, he said, “Are you crazy?” and then enjoyed the wine immensely. That bottle remains a treasured memento.

Dad ate suppers with us, wearing his royal blue spring jacket (as our home's cool temperature did not mix well with his poor circulation). He told bad jokes and entertaining stories, mainly about serving in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps during the Great Depression. He had asked for a tour in the Pacific Northwest, but when the trains unloaded, the young men found themselves in Vermont and later Maine.

Dad and Dave once put lobsters in a pot, and we heard a high pitched moan. Dave and I cringed, thinking the lobsters were crying out for mercy. Dad's Irish eyes twinkled; he had made the noise himself.

My uncles drove Dad to the dog track or casino, right after he got “tanked up” from his monthly transfusions.

Dad devotedly visited Mom every day, shuffling down the hall while shouldering his portable oxygen tank. The staff gently said he did not have to come every day, but he did. The day Dad said, “I will never golf again,” I denied it vehemently, but he was right.

Six weeks before my cousin Father Mark Jette Mark married me and Dave in 1977, Dad's heart attack had sent him into disability and retirement. Doctor Takata performed five heart bypasses and assured Mom that Dad would not only walk me down the aisle, but dance at my wedding. Doctor Takata's gift was a further 18 years with Dad.

Pneumonia finally brought Dad to Hartford Hospital's emergency room, where we chatted and Dad sat reading the New Britain Herald. His congestive heart failure stemmed from years of smoking and welding around asbestos. The covering cardiologist arrived, questioned Dad's symptoms, then asked if he had a living will. Either that question confused him and triggered something in his brain, or it was sheer bad timing, but Dad never spoke coherently again. Over the next three days, the only word I could understand was “Mommy.” I asked the cardiac nurse if I should bring his clothes, and she abruptly said no.

I was not with Dad the next morning when he died. Our close friend and Dad's tenant Steve was the last friend or family member to see Dad alive. Father Mark celebrated Dad's funeral Mass, and read Chappy jokes from his handwritten joke notebook found in his bureau drawer. An Irish small farmer was touring a Texan's huge ranch. The Texan says, “ I can drive my truck all day, and only be halfway across my land.” The Irishman says, “Sure, and I had a truck like that once meself.”

A woman once asked why I seemed so sad, and I said, “I am worn out taking my Dad to all his doctor's appointments and monthly blood transfusions.” She replied “Enjoy him while you can. My dad died seven years ago today, and I still miss him.” I took her at her word during Dad's last year.

We continue to celebrate Dad's life and spirit. His blue recliner has pride of place in our living room. The hand-forged nutcracker of a lady's shapely legs reclines in the holiday nutbowl.

Dave now uses the Chappy method of fire tending, after years of overthinking. When would Chappy toss a log onto a fire to keep it blazing? Now.

We recite punchlines from Dad's bad and sometimes incomprehensible jokes to each other. “You know what the Irishman says? “I don't like to eat meat, but I love ham [pronounced hahm].”

I treasure this handwritten note found in Dad's car glovebox: “I love you both.” When did he write that? When did he think we would read it? It does not matter. Dad, I love you back always, with all my heart.

I married my father. There is no higher compliment I could give my husband.

I sat in my childhood home in New Britain, Connecticut, in Dad's 1960s-decorated kitchen, counting his weekly pills into morning and evening doses, and reflected that I was now taking care of Charles “Chappy” O'Sullivan, who had taken care of me his entire life. We had just returned from making pre-paid funeral arrangements for both him and Mom, whose debilitating stroke had left her in a nursing home, never to recover or return home. Dad would be waked from the Irish funeral home in town, Mom from the Swedish.

My year-long layoff from Aetna from dried-up project funding would gift me with time to enjoy Dad's company as never before.

Dad and I reviewed the contents of their safe deposit box, including details of how my birth parents gifted me to my parents, and Mom's letter to the adoption agency presciently recounting what a wonderful father Dad would make.

I took Dad to lunches, and once ordered a pricey wine just to “get his goat.” Sure enough, he said, “Are you crazy?” and then enjoyed the wine immensely. That bottle remains a treasured memento.

Dad ate suppers with us, wearing his royal blue spring jacket (as our home's cool temperature did not mix well with his poor circulation). He told bad jokes and entertaining stories, mainly about serving in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps during the Great Depression. He had asked for a tour in the Pacific Northwest, but when the trains unloaded, the young men found themselves in Vermont and later Maine.

Dad and Dave once put lobsters in a pot, and we heard a high pitched moan. Dave and I cringed, thinking the lobsters were crying out for mercy. Dad's Irish eyes twinkled; he had made the noise himself.

My uncles drove Dad to the dog track or casino, right after he got “tanked up” from his monthly transfusions.

Dad devotedly visited Mom every day, shuffling down the hall while shouldering his portable oxygen tank. The staff gently said he did not have to come every day, but he did. The day Dad said, “I will never golf again,” I denied it vehemently, but he was right.

Six weeks before my cousin Father Mark Jette Mark married me and Dave in 1977, Dad's heart attack had sent him into disability and retirement. Doctor Takata performed five heart bypasses and assured Mom that Dad would not only walk me down the aisle, but dance at my wedding. Doctor Takata's gift was a further 18 years with Dad.

Pneumonia finally brought Dad to Hartford Hospital's emergency room, where we chatted and Dad sat reading the New Britain Herald. His congestive heart failure stemmed from years of smoking and welding around asbestos. The covering cardiologist arrived, questioned Dad's symptoms, then asked if he had a living will. Either that question confused him and triggered something in his brain, or it was sheer bad timing, but Dad never spoke coherently again. Over the next three days, the only word I could understand was “Mommy.” I asked the cardiac nurse if I should bring his clothes, and she abruptly said no.

I was not with Dad the next morning when he died. Our close friend and Dad's tenant Steve was the last friend or family member to see Dad alive. Father Mark celebrated Dad's funeral Mass, and read Chappy jokes from his handwritten joke notebook found in his bureau drawer. An Irish small farmer was touring a Texan's huge ranch. The Texan says, “ I can drive my truck all day, and only be halfway across my land.” The Irishman says, “Sure, and I had a truck like that once meself.”

A woman once asked why I seemed so sad, and I said, “I am worn out taking my Dad to all his doctor's appointments and monthly blood transfusions.” She replied “Enjoy him while you can. My dad died seven years ago today, and I still miss him.” I took her at her word during Dad's last year.

We continue to celebrate Dad's life and spirit. His blue recliner has pride of place in our living room. The hand-forged nutcracker of a lady's shapely legs reclines in the holiday nutbowl.

Dave now uses the Chappy method of fire tending, after years of overthinking. When would Chappy toss a log onto a fire to keep it blazing? Now.

We recite punchlines from Dad's bad and sometimes incomprehensible jokes to each other. “You know what the Irishman says? “I don't like to eat meat, but I love ham [pronounced hahm].”

I treasure this handwritten note found in Dad's car glovebox: “I love you both.” When did he write that? When did he think we would read it? It does not matter. Dad, I love you back always, with all my heart.

I married my father. There is no higher compliment I could give my husband.

"Bridgeport or Bust" by Allison Keeton

Two or three times a year, my parents and I took a trip to visit my father's parents in Bridgeport. As a seven year old, this was the longest trip I made on a regular basis, and I planned for days: what to wear, what to bring for the ride down and for my grandparents' tiny apartment, and what snacks to have in the back seat.

My grandparents were in their eighties. They had a nice house with a steep staircase but moved into a first floor apartment when my grandmother broke her hip. Their new neighborhood and its loud music and crowded streets frightened me. I was from Willington, a town of five thousand with quiet backyards. “The sticks” as my grandfather called it. In Bridgeport, I heard the scream of the sirens and the yelling of the neighbors. I liked the Spanish, though. It reminded me of the Shop Rite in Willimantic.

I asked my parents how many days it took to get to Bridgeport. I guessed three. "An hour and a half," my father said.

On the day of the trip, I placed one of my wooden chairs purchased at a gas station in the backseat. I wanted a good view. Seatbelt use in my family was unheard of until I took Driver's Ed ten years later. I piled up my books – two mysteries in case I finished the first one and three puzzle books – and pencils, pens, and markers. Next to the books was my own cooler with bite-sized ham and cheese sandwiches, homemade chocolate chip cookies, cut up apple sprinkled with cinnamon and sugar, and a thermos of lemonade. My school bag was filled with a change of clothes and a couple of card games like Old Maid and Go Fish.

On the ride down, we practiced the state capitals from yellowing flash cards. My mother called out the state, and I named the capital. Then we reversed it. These cards were so old that they didn't include Alaska and Hawaii. Thankfully my parents knew Juneau and Honolulu. We completed the capitals by New Haven in time for me to stare at a park's statue overlooking the highway. "Someone fell off that cliff playing Frisbee," my mother said on one trip. On another, "They found the strangled body right near that statue," my father whispered. (To this day, I am still mesmerized by that statue and have never visited East Rock Park.)

If I saw the statue, it meant my father had taken the main highway through Hartford to I-95 South, which really goes west in Connecticut. I preferred the Merritt Parkway with its tree-lined drive and no trucks, but it dumped us on the wrong (nice) side of town, Pop said.

The scenery from I-95 was ugly, and, finally, after passing numerous wrecking balls at junk yards, we arrived. My grandparents peered out their front door and waved. I was glad my father parked in front—I didn't want anyone to break into the car and steal my little chair like they tried to steal someone's radio the last time we were visiting.

We unloaded groceries for my grandparents and brought in almost all of my backseat items. It felt like we spent a couple of days in their apartment, but it was only a few hours. In short years to come, my grandparents would be gone, along with the reason to make this trip, but I didn’t know that then.

My grandparents were in their eighties. They had a nice house with a steep staircase but moved into a first floor apartment when my grandmother broke her hip. Their new neighborhood and its loud music and crowded streets frightened me. I was from Willington, a town of five thousand with quiet backyards. “The sticks” as my grandfather called it. In Bridgeport, I heard the scream of the sirens and the yelling of the neighbors. I liked the Spanish, though. It reminded me of the Shop Rite in Willimantic.

I asked my parents how many days it took to get to Bridgeport. I guessed three. "An hour and a half," my father said.

On the day of the trip, I placed one of my wooden chairs purchased at a gas station in the backseat. I wanted a good view. Seatbelt use in my family was unheard of until I took Driver's Ed ten years later. I piled up my books – two mysteries in case I finished the first one and three puzzle books – and pencils, pens, and markers. Next to the books was my own cooler with bite-sized ham and cheese sandwiches, homemade chocolate chip cookies, cut up apple sprinkled with cinnamon and sugar, and a thermos of lemonade. My school bag was filled with a change of clothes and a couple of card games like Old Maid and Go Fish.

On the ride down, we practiced the state capitals from yellowing flash cards. My mother called out the state, and I named the capital. Then we reversed it. These cards were so old that they didn't include Alaska and Hawaii. Thankfully my parents knew Juneau and Honolulu. We completed the capitals by New Haven in time for me to stare at a park's statue overlooking the highway. "Someone fell off that cliff playing Frisbee," my mother said on one trip. On another, "They found the strangled body right near that statue," my father whispered. (To this day, I am still mesmerized by that statue and have never visited East Rock Park.)

If I saw the statue, it meant my father had taken the main highway through Hartford to I-95 South, which really goes west in Connecticut. I preferred the Merritt Parkway with its tree-lined drive and no trucks, but it dumped us on the wrong (nice) side of town, Pop said.

The scenery from I-95 was ugly, and, finally, after passing numerous wrecking balls at junk yards, we arrived. My grandparents peered out their front door and waved. I was glad my father parked in front—I didn't want anyone to break into the car and steal my little chair like they tried to steal someone's radio the last time we were visiting.

We unloaded groceries for my grandparents and brought in almost all of my backseat items. It felt like we spent a couple of days in their apartment, but it was only a few hours. In short years to come, my grandparents would be gone, along with the reason to make this trip, but I didn’t know that then.

"Closing the Window" by Leta Marks

Sitting on the chair with my head resting on Alby’s chest, I squinted at my books on the study shelves, trying to recognize their titles. I wished the chatter from our children and grandchildren drifting in from the dining room and a Mozart quartet playing in the room could distract me from focusing on the shallow breathing of my husband, who lay inert in his hospital bed. In any case, I felt blessed having our children home from faraway places.

It seemed longer, but only days ago, I sat next to him like this in the E.R., waiting for test results before phoning our family. Following long consultations with doctors, I called our three younger kids in Seattle and Boston—easier to reach than Jonny in Bucharest where it was midnight. I’ve hated that as a foreign-service officer for fifteen years he’s lived abroad, not experiencing daily his dad’s deterioration. Like me he’s a denier, processes slowly, but mostly he fantasizes his dad’s mowing the lawn, chewing his corncob pipe, or trekking thirty mile on his bike. When finalizing my birthday family reunion, I was shocked that Jonny expected me to take Alby, became insistent even after I explained the twenty-four-hour skilled-nursing needs. Denying Alby’s illness, could he accept his death? I dialed his number.

“Oh, hi Mom, what’s up?” he said when he heard my voice.

“Well…I’m with Dad in the emergency room….He’s in a coma…has been all day….I’m so sorry, but the doctor and your sibs agree we…should take him home…let him…go peacefully.”

“Mom, NO,” he cried. “I don’t agree with this decision. You know how I feel.” Yes, I knew. I remember sitting at dinner when Jonny at six learned steak came from a dead cow. At sixteen he became a vegetarian, letting spiders and mosquitoes live rather than swat them. I recall his protesting as an adult, euthanizing his cat.

“But, Jonny, his system’s shut down. He’ll need…a feeding tube and dialysis...forever.”

“Don’t let him die. Give him a chance. He might get better.”

“I know this seems harsh, Jonny…please try to understand…” I was crying and trying to convince him simultaneously. “The doctor said treatment would prolong dying…be painful….” My legs felt like mush. I slid down the wall and sat on the cold tile.

“Mom, don’t give up on him.” he screamed.

“He can’t swallow…water spills from his mouth. He chokes, dribbles…needs a bib. He’d hate this indignity…if he knew....”

“Mom, I know it’s hard for you. I’m sorry.”

“It’s not about me. It’s about him. You haven’t seen what life’s dealt him.”

“Just try the feeding tube and dialysis. Maybe he’ll respond…give him time.”

I wanted to tell him the Talmudic parable about a dying man’s wife’s choice in closing the window if heartbeat-like sounds of a woodchopper splitting logs outside kept him alive.

Then, perhaps too abruptly, I said, “I’m taking him home, Jonny. I love you…I love your dad."

…Now our family was together. I’m glad they arrived home quickly, especially Jonny, who slowly realized treatment couldn’t revive his dad to any quality living. Since the ambulance brought him home, we’d held vigil nine days, turning him, moistening his mouth with green lollipop swabs, and dropped morphine into his cheek to ease his journey. Our daughter Cathy dragged in extra chairs, and like nineteenth century death-bed portraits, we gathered around his bed talking and reminiscing, wondering if he heard us. He lay limp without moving limbs or eyes. We invited friends to say goodbye. Each took his hand, whispered words, and silently departed.

On this tenth day, in the quiet room alone with Alby my cheek on his chest, I thought of years in this home, his mending everything with coat hangers, and laughing at his own corny jokes. Memories flashed of our children growing up and moving on, births of grandchildren, and trips we’ve taken—especially to Madras where I pushed his wheel chair through muddy streets, dodging sleeping sacred cows. How lucky we’ve been in spite of this demon disease. For twenty years I’ve watched him drifting away into the labyrinth of darkness, regressing into some stone figure not opening his eyes or speaking as that rapacious Parkinson’s disease attacked his brain, masked his once expressive face, and slowed his body until he couldn’t move, didn’t know me at all. This night, I tried not to dwell on that. I told myself to pack away the nightmare visions, not cloud our last days. I wanted to savor this unplanned family reunion. From the kitchen I heard dishes clattering as the kids finished their lasagna. I hadn’t wanted to join them, content to hear laughing from afar.

Then a strange event occurred: Cleo, our twelve-year-old Siamese cat appeared at the study door, stood momentarily, entered, and then silently marked all four walls of the room by circling the perimeter—just once—around the bed, under chairs, under tables in her final sweep before leaving, never to enter that room again. At that moment, I didn’t know what it meant.

Cathy entered the room, put her arm on mine and said, “Mom, get some sleep; I’ll sit with Dad.” How good the cool sheets felt on my burning face. I slept...

…Until Cathy’s soft voice announced from the doorway, “Mom…he’s gone,”

“My God,” I said throwing off the covers. “The cat knew the window was closing.”

It seemed longer, but only days ago, I sat next to him like this in the E.R., waiting for test results before phoning our family. Following long consultations with doctors, I called our three younger kids in Seattle and Boston—easier to reach than Jonny in Bucharest where it was midnight. I’ve hated that as a foreign-service officer for fifteen years he’s lived abroad, not experiencing daily his dad’s deterioration. Like me he’s a denier, processes slowly, but mostly he fantasizes his dad’s mowing the lawn, chewing his corncob pipe, or trekking thirty mile on his bike. When finalizing my birthday family reunion, I was shocked that Jonny expected me to take Alby, became insistent even after I explained the twenty-four-hour skilled-nursing needs. Denying Alby’s illness, could he accept his death? I dialed his number.

“Oh, hi Mom, what’s up?” he said when he heard my voice.

“Well…I’m with Dad in the emergency room….He’s in a coma…has been all day….I’m so sorry, but the doctor and your sibs agree we…should take him home…let him…go peacefully.”

“Mom, NO,” he cried. “I don’t agree with this decision. You know how I feel.” Yes, I knew. I remember sitting at dinner when Jonny at six learned steak came from a dead cow. At sixteen he became a vegetarian, letting spiders and mosquitoes live rather than swat them. I recall his protesting as an adult, euthanizing his cat.

“But, Jonny, his system’s shut down. He’ll need…a feeding tube and dialysis...forever.”

“Don’t let him die. Give him a chance. He might get better.”

“I know this seems harsh, Jonny…please try to understand…” I was crying and trying to convince him simultaneously. “The doctor said treatment would prolong dying…be painful….” My legs felt like mush. I slid down the wall and sat on the cold tile.

“Mom, don’t give up on him.” he screamed.

“He can’t swallow…water spills from his mouth. He chokes, dribbles…needs a bib. He’d hate this indignity…if he knew....”

“Mom, I know it’s hard for you. I’m sorry.”

“It’s not about me. It’s about him. You haven’t seen what life’s dealt him.”

“Just try the feeding tube and dialysis. Maybe he’ll respond…give him time.”

I wanted to tell him the Talmudic parable about a dying man’s wife’s choice in closing the window if heartbeat-like sounds of a woodchopper splitting logs outside kept him alive.

Then, perhaps too abruptly, I said, “I’m taking him home, Jonny. I love you…I love your dad."

…Now our family was together. I’m glad they arrived home quickly, especially Jonny, who slowly realized treatment couldn’t revive his dad to any quality living. Since the ambulance brought him home, we’d held vigil nine days, turning him, moistening his mouth with green lollipop swabs, and dropped morphine into his cheek to ease his journey. Our daughter Cathy dragged in extra chairs, and like nineteenth century death-bed portraits, we gathered around his bed talking and reminiscing, wondering if he heard us. He lay limp without moving limbs or eyes. We invited friends to say goodbye. Each took his hand, whispered words, and silently departed.

On this tenth day, in the quiet room alone with Alby my cheek on his chest, I thought of years in this home, his mending everything with coat hangers, and laughing at his own corny jokes. Memories flashed of our children growing up and moving on, births of grandchildren, and trips we’ve taken—especially to Madras where I pushed his wheel chair through muddy streets, dodging sleeping sacred cows. How lucky we’ve been in spite of this demon disease. For twenty years I’ve watched him drifting away into the labyrinth of darkness, regressing into some stone figure not opening his eyes or speaking as that rapacious Parkinson’s disease attacked his brain, masked his once expressive face, and slowed his body until he couldn’t move, didn’t know me at all. This night, I tried not to dwell on that. I told myself to pack away the nightmare visions, not cloud our last days. I wanted to savor this unplanned family reunion. From the kitchen I heard dishes clattering as the kids finished their lasagna. I hadn’t wanted to join them, content to hear laughing from afar.

Then a strange event occurred: Cleo, our twelve-year-old Siamese cat appeared at the study door, stood momentarily, entered, and then silently marked all four walls of the room by circling the perimeter—just once—around the bed, under chairs, under tables in her final sweep before leaving, never to enter that room again. At that moment, I didn’t know what it meant.

Cathy entered the room, put her arm on mine and said, “Mom, get some sleep; I’ll sit with Dad.” How good the cool sheets felt on my burning face. I slept...

…Until Cathy’s soft voice announced from the doorway, “Mom…he’s gone,”

“My God,” I said throwing off the covers. “The cat knew the window was closing.”

"The Gift" by Carol Parker

It's the morning of my fortieth birthday, and the day I'll leave my husband. He sits smoking cigarettes at one end of the kitchen table; I'm at the other, drinking coffee. "I've put up with your shit for thirteen years. I'm not taking it anymore."

But I don't say that. Instead, I say, “I’m leaving.”

A fist slams, sending shock waves through walls. As if in slow motion but faster than I can move, he crosses the table and yanks me from the chair by my waist-long braid. “You’re not getting out of this marriage.” He crashes me to the floor; I slide on my stomach toward the phone, but he snaps the cord.

I was twenty-six. My girlfriend and I spent the weekend in Montreal and were riding Amtrak home to Hartford. It was crowded, so we sat in the bar car. As I stood in line for service, I saw the bartender, his high cheekbones and almond-like eyes.

"What would you like, Miss?"

"Just some conversation," I answered, shocked I'd said it. "Two coffees, please."

He found us during his break. While Audrey napped, Barry and I talked as if we were the only people on the train and that we'd met before. He noticed me shivering so he draped his peacoat over my shoulders, insisting.

For the next three months we wove our lives together with phone calls and rendezvous in Connecticut and D.C., where he lived. I loved the way he mingled easily with people; I always felt like I was dredging my brain to make conversation. Barry knew what to say and how to gain favor. I was in heaven when he transferred to New Haven; three months later we eloped.

Newlyweds, we were going away for the weekend. On our way out of town, we pulled through McDonalds. While waiting to get back into traffic, I changed the radio station, and his hand ripped across my face.

Seven-year-old Stephanie sees us. Her eight-year-old brother is at a friend's house. "Get help!” I scream to my daughter, who's sobbing in the middle of the room.

When the children were young, we often drove to the Connecticut shoreline, where Barry discovered a perfect spot for crabbing. With Greg on his shoulders and Stephanie on mine, we walked the half-mile through woods, to the water; the kids climbed rocks or waded in low tide, while Barry and I baited the traps. When they asked how the crabs fit inside, he took time to explain. Barry and I were tender with each other. "Carol, you're my wife for life. Look at our beautiful family. It doesn't get better than this."

He drags me into the bedroom. “I’m going to kill you." Straddling me on the bed, hands cuffed around my wrists, he forces himself on me. Vacant eyes stare through me as if I'm a figment of my imagination. I cry out, but only the woods hear.

I never knew when Barry would snap. Three years earlier, he'd cornered me in the den. I grabbed the nearest weapon, a television, and flung it at him with adrenalin force, escaping down a flight of stairs. I drove in a daze, telling myself I should find the police; another voice inside said not to turn him in. I ended up at the babysitter’s; two weeks later, bruises fading, I went back.

Friends stopped calling, for friendships need nurturing and take time to maintain; I had no extra to give, what with my job, two young children, and a husband I was committed to fixing. His need to control stemmed from his parents, who trained their kids as if they were dogs instead of children.

His fingers are digging into my windpipe. I'll never see Greg and Steph again.

As if I've separated from my body, I'm floating, watching myself die.

When I was four, I found my brother in his crib. At first I didn't know he was dead. Peering through the slats, I saw yellow footie pajamas. "Jimmy," I whispered, reaching in. His fingers were cold. I saw his face and ran to my mother.

"Mommy, come see. Jimmy's blue."

I watched her scoop him up, her face shriveling as she shrieked, "Get help!"

My sisters and I were shuffled between home and neighbors. I sat close-mouthed, sobbing and rocking under their table while my parents tended to my brother's death. We never talked about it. Self-blame grew inside me, metastasizing to the need to rescue others, martyring myself. On the eve of my fortieth birthday, reflecting on the prison that had become my life, I had an epiphany: I'm not responsible for what happened to Jimmy.

I want to say, "Barry, for my birthday, I'm giving myself the gift of empowerment, so I'm leaving." But I don't tell the truth. Gagging and gasping, I spew out, "I love you, Barry. I'll never leave."

His grip softens, then tightens. I whisper, “Let me find Stephanie.” I pick up my aching body and walk out the front door, closing it gently behind.

He’s breathing on my neck; or do I imagine he's chasing me? Stumbling down the driveway, I feel him at my back. I'm at the neighbor's door, fumbling; it doesn't budge. Then it opens, at first a crack. I savor this moment, mother and daughter together; releasing the shackles, I grow my power.

But I don't say that. Instead, I say, “I’m leaving.”

A fist slams, sending shock waves through walls. As if in slow motion but faster than I can move, he crosses the table and yanks me from the chair by my waist-long braid. “You’re not getting out of this marriage.” He crashes me to the floor; I slide on my stomach toward the phone, but he snaps the cord.

I was twenty-six. My girlfriend and I spent the weekend in Montreal and were riding Amtrak home to Hartford. It was crowded, so we sat in the bar car. As I stood in line for service, I saw the bartender, his high cheekbones and almond-like eyes.

"What would you like, Miss?"

"Just some conversation," I answered, shocked I'd said it. "Two coffees, please."

He found us during his break. While Audrey napped, Barry and I talked as if we were the only people on the train and that we'd met before. He noticed me shivering so he draped his peacoat over my shoulders, insisting.

For the next three months we wove our lives together with phone calls and rendezvous in Connecticut and D.C., where he lived. I loved the way he mingled easily with people; I always felt like I was dredging my brain to make conversation. Barry knew what to say and how to gain favor. I was in heaven when he transferred to New Haven; three months later we eloped.

Newlyweds, we were going away for the weekend. On our way out of town, we pulled through McDonalds. While waiting to get back into traffic, I changed the radio station, and his hand ripped across my face.

Seven-year-old Stephanie sees us. Her eight-year-old brother is at a friend's house. "Get help!” I scream to my daughter, who's sobbing in the middle of the room.

When the children were young, we often drove to the Connecticut shoreline, where Barry discovered a perfect spot for crabbing. With Greg on his shoulders and Stephanie on mine, we walked the half-mile through woods, to the water; the kids climbed rocks or waded in low tide, while Barry and I baited the traps. When they asked how the crabs fit inside, he took time to explain. Barry and I were tender with each other. "Carol, you're my wife for life. Look at our beautiful family. It doesn't get better than this."

He drags me into the bedroom. “I’m going to kill you." Straddling me on the bed, hands cuffed around my wrists, he forces himself on me. Vacant eyes stare through me as if I'm a figment of my imagination. I cry out, but only the woods hear.

I never knew when Barry would snap. Three years earlier, he'd cornered me in the den. I grabbed the nearest weapon, a television, and flung it at him with adrenalin force, escaping down a flight of stairs. I drove in a daze, telling myself I should find the police; another voice inside said not to turn him in. I ended up at the babysitter’s; two weeks later, bruises fading, I went back.

Friends stopped calling, for friendships need nurturing and take time to maintain; I had no extra to give, what with my job, two young children, and a husband I was committed to fixing. His need to control stemmed from his parents, who trained their kids as if they were dogs instead of children.

His fingers are digging into my windpipe. I'll never see Greg and Steph again.

As if I've separated from my body, I'm floating, watching myself die.

When I was four, I found my brother in his crib. At first I didn't know he was dead. Peering through the slats, I saw yellow footie pajamas. "Jimmy," I whispered, reaching in. His fingers were cold. I saw his face and ran to my mother.

"Mommy, come see. Jimmy's blue."

I watched her scoop him up, her face shriveling as she shrieked, "Get help!"

My sisters and I were shuffled between home and neighbors. I sat close-mouthed, sobbing and rocking under their table while my parents tended to my brother's death. We never talked about it. Self-blame grew inside me, metastasizing to the need to rescue others, martyring myself. On the eve of my fortieth birthday, reflecting on the prison that had become my life, I had an epiphany: I'm not responsible for what happened to Jimmy.

I want to say, "Barry, for my birthday, I'm giving myself the gift of empowerment, so I'm leaving." But I don't tell the truth. Gagging and gasping, I spew out, "I love you, Barry. I'll never leave."

His grip softens, then tightens. I whisper, “Let me find Stephanie.” I pick up my aching body and walk out the front door, closing it gently behind.

He’s breathing on my neck; or do I imagine he's chasing me? Stumbling down the driveway, I feel him at my back. I'm at the neighbor's door, fumbling; it doesn't budge. Then it opens, at first a crack. I savor this moment, mother and daughter together; releasing the shackles, I grow my power.

"So That You Will Hear Me" by Bessy Reyna

There are words we say, and, as soon as they escape our lips, we wish we could vacuum them back. Retrieve them before they can alter reality. But, we are compelled to say them because otherwise the thoughts they express work on us like cavities weakening us from within.

That’s why I had to tell Adriana that I was in love with her, because I thought that by saying those words I would begin to understand what was happening to me, because I was already in my early twenties and I had never felt that way about a woman before. “Creo que me estoy enamorando de tí.”

From the moment we met we were inseparable. All of Panama City became our playground. We created a routine: Late afternoons I picked her up at her job in the office of one of the many newspapers published in the city, then go to dinner or sit at the Boulevard Café drinking cappuccinos while looking at the profiles of shrimp boats coming back to the docks. Other times, we sipped wine while discussing the latest French or Italian movie we had just seen, or reading Neruda’s Veinte Poemas de Amor to each other. However, the highlight of our encounters was to put together a picnic basket and drive to a hill in Paitilla, sit on a blanket on the grass and while eating admire the glorious sunsets spreading reds and oranges over the Pacific Ocean below.

Sounds romantic, but it wasn’t. Not really. At first, it was simply two young women enjoying each other’s company, savoring a new friendship and admiring the beauty of nature surrounding us.

When Adriana and I first met, she had been living in Rome for several years. Her parents had taken her to Italy on the pretense of a family vacation. When they arrived, she learned that they had secretly rented an apartment for her. Their plotting was out of a romantic novel. They wanted to remove her from the temptation of a man of whom they disapproved. One week she was living in Panama, and the next she was left behind in Italy, having to quickly adapt to another culture and learn a new language.

No wonder she often used the word betrayal when she mentioned her parents. If your parents can betray you like that, who else will be next? “Imagine doing that to your daughter?” she asked me once. The ironic part was that while her parents plotted, Adriana was already planning to break up with the guy. But we lived in a culture where fathers thought they owned and controlled their daughters’ destinies. “As long as you live in my house…” was their mantra, selectively applied only to daughters.

Adriana had long black hair, tied behind her back, framing the lovely white skin of her neck. There was a delicacy about her like the ethereal Geishas in the ukiyo-e prints I admire. Her dimpled smile and contagious laughter made me forget about everything else going on in my life, a job I hated, mediocre teachers at the university, and a family environment I couldn’t wait to get away from.

One day, as we sat side by side on a blanket at Paitilla, I was overwhelmed with the desire to touch her, caress her. It was such an unusual, strange and unsettling sensation that I became uncharacteristically quiet for the rest of the afternoon. I was quiet as I drove her home. She asked if there was something wrong but I didn’t know what to say. How could I convey to her an emotion I couldn’t understand? I had never felt embarrassed by my feelings for men before. I had been taught what to expect from an early age, but Adriana was a vortex.

At the beginning of our friendship, we made fun of each other’s personalities, laughing at how uncanny it was that we both seemed to take the same photographs, from the same angles, or underlined the same paragraphs in a book we had read.

Before we met, I had never paid attention to horoscopes, but now we read them together because our July birthdays were five days apart. We joked that was probably the reason for the mirror images we had become. I had never found that kind of oneness with anyone before. We isolated ourselves from other people while my friends complained about my absence.

Adriana and I created a barrier around ourselves, pretending to be Italian tourists visiting Panama, speaking in Italian, a language I had started to learn the year before. Ho visto quello che hai fatto cattiva. Andiamo? Adriana taught me how deliciously wicked it is to hide behind a language those around you don’t understand.

The afternoon I dared to say “I think I am in love with you” we had been watching one of those beautiful Panamanian sunsets which seemed to change the feel of the city, softening the metal and glass skyscrapers overlooking the bay.

If my words upset her she didn’t show any emotion at first. But, after a short time she asked me to take her home.

It was later when she wouldn’t take my calls or see me that I knew I had lost her. Was my expression of love perceived as yet another form of betrayal? The painful cavity I had tried to fill with those words grew large with loneliness and longing.

She left the country.

Decades would pass before I learned that she too had moved to the US, that she married, divorced, married again, and had children.

I called her and after that, we wrote to each other, enjoying retracing our lives and updating our stories. She sent me a recording of a radio interview she conducted with gay activists as if to say “Now I understand.”

I listened to her voice, the intensity with which she asked questions, while pretending we were back at the Café, or sitting overlooking the ocean, picnicking in Paitilla, and laughing. Her voice talking to me like the day before I said, “Creo que estoy enamorándome de tí. I think I am falling in love with you.”

Those words I said, and, as soon as they escaped from my lips, they made me lose her. Ya no la quiero es cierto, pero cuanto la quise. Mi voz buscaba el viento para tocar su oido.

That’s why I had to tell Adriana that I was in love with her, because I thought that by saying those words I would begin to understand what was happening to me, because I was already in my early twenties and I had never felt that way about a woman before. “Creo que me estoy enamorando de tí.”

From the moment we met we were inseparable. All of Panama City became our playground. We created a routine: Late afternoons I picked her up at her job in the office of one of the many newspapers published in the city, then go to dinner or sit at the Boulevard Café drinking cappuccinos while looking at the profiles of shrimp boats coming back to the docks. Other times, we sipped wine while discussing the latest French or Italian movie we had just seen, or reading Neruda’s Veinte Poemas de Amor to each other. However, the highlight of our encounters was to put together a picnic basket and drive to a hill in Paitilla, sit on a blanket on the grass and while eating admire the glorious sunsets spreading reds and oranges over the Pacific Ocean below.

Sounds romantic, but it wasn’t. Not really. At first, it was simply two young women enjoying each other’s company, savoring a new friendship and admiring the beauty of nature surrounding us.

When Adriana and I first met, she had been living in Rome for several years. Her parents had taken her to Italy on the pretense of a family vacation. When they arrived, she learned that they had secretly rented an apartment for her. Their plotting was out of a romantic novel. They wanted to remove her from the temptation of a man of whom they disapproved. One week she was living in Panama, and the next she was left behind in Italy, having to quickly adapt to another culture and learn a new language.

No wonder she often used the word betrayal when she mentioned her parents. If your parents can betray you like that, who else will be next? “Imagine doing that to your daughter?” she asked me once. The ironic part was that while her parents plotted, Adriana was already planning to break up with the guy. But we lived in a culture where fathers thought they owned and controlled their daughters’ destinies. “As long as you live in my house…” was their mantra, selectively applied only to daughters.

Adriana had long black hair, tied behind her back, framing the lovely white skin of her neck. There was a delicacy about her like the ethereal Geishas in the ukiyo-e prints I admire. Her dimpled smile and contagious laughter made me forget about everything else going on in my life, a job I hated, mediocre teachers at the university, and a family environment I couldn’t wait to get away from.

One day, as we sat side by side on a blanket at Paitilla, I was overwhelmed with the desire to touch her, caress her. It was such an unusual, strange and unsettling sensation that I became uncharacteristically quiet for the rest of the afternoon. I was quiet as I drove her home. She asked if there was something wrong but I didn’t know what to say. How could I convey to her an emotion I couldn’t understand? I had never felt embarrassed by my feelings for men before. I had been taught what to expect from an early age, but Adriana was a vortex.

At the beginning of our friendship, we made fun of each other’s personalities, laughing at how uncanny it was that we both seemed to take the same photographs, from the same angles, or underlined the same paragraphs in a book we had read.

Before we met, I had never paid attention to horoscopes, but now we read them together because our July birthdays were five days apart. We joked that was probably the reason for the mirror images we had become. I had never found that kind of oneness with anyone before. We isolated ourselves from other people while my friends complained about my absence.

Adriana and I created a barrier around ourselves, pretending to be Italian tourists visiting Panama, speaking in Italian, a language I had started to learn the year before. Ho visto quello che hai fatto cattiva. Andiamo? Adriana taught me how deliciously wicked it is to hide behind a language those around you don’t understand.

The afternoon I dared to say “I think I am in love with you” we had been watching one of those beautiful Panamanian sunsets which seemed to change the feel of the city, softening the metal and glass skyscrapers overlooking the bay.

If my words upset her she didn’t show any emotion at first. But, after a short time she asked me to take her home.

It was later when she wouldn’t take my calls or see me that I knew I had lost her. Was my expression of love perceived as yet another form of betrayal? The painful cavity I had tried to fill with those words grew large with loneliness and longing.

She left the country.

Decades would pass before I learned that she too had moved to the US, that she married, divorced, married again, and had children.

I called her and after that, we wrote to each other, enjoying retracing our lives and updating our stories. She sent me a recording of a radio interview she conducted with gay activists as if to say “Now I understand.”

I listened to her voice, the intensity with which she asked questions, while pretending we were back at the Café, or sitting overlooking the ocean, picnicking in Paitilla, and laughing. Her voice talking to me like the day before I said, “Creo que estoy enamorándome de tí. I think I am falling in love with you.”

Those words I said, and, as soon as they escaped from my lips, they made me lose her. Ya no la quiero es cierto, pero cuanto la quise. Mi voz buscaba el viento para tocar su oido.

"An Uncommon Language" by Phyllis Satter

“Go where?”

“To the backyard,” I pointed by nodding in that direction as I balanced our iced teas on a tray.

“You mean the garden?” asked Keith, my new British boyfriend. I often needed to explain our American form of his language to him.

“We call it the yard here, Keith.”

He shuddered, “Yard is an ugly word for such a lovely place.”

Slowly, I explained, “Keith, here it’s the space behind the house, where kids play, women hang out the washing, and we’ll have our drinks.” I tried to be a patient teacher. I never imagined part of our new relationship would find me teaching English to an Englishman.

He curled his lip in disgust. “In England, yards are paved with tarmac, with a few dustbins in a corner. Yard is too ugly.” I liked the way he wrinkled his nose. My mind strayed from the lesson.

Dustbins, tarmac, where to begin? Keith and I often lapsed into our version of the Revolutionary War over linguistic differences.

Jello, jelly, and jam launched another skirmish. Brits eat jelly for dessert: here we put it on our toast. They’re happy to say jam when they’re spreading either jelly or preserves.

We had met in the fall of 1960 at Swarthmore College, Keith and I, at 21 and 20, he an exchange student from England, I a junior. In our first encounter, words and language formed the heart of the matter. One Saturday night, my friend Izzy and I sat studying European history together in Commons, a cavernous, high-ceilinged social center in Parrish Hall. By day, the high uncurtained Georgian windows filled the space with light. At night, the glass turned ink-black, and the room sank deep in gloom, except where a few floor lamps with their always cockeyed shades dotted the floor with narrow pools of dim light. The almost-fog of our cigarette smoke drifted through those pools.

Izzy looked up from her book. Annoyed by the need to interrupt her reading, she demanded, “What does this word mean, obstreperous?”

“What’s the context? Read me the sentence it’s in.”

Izzy read it, something about the conduct of British politicians in the House of Lords, debating hotly. Instead of supplying Izzy with another word, I began to act out the meaning, mouthing silent shouts, gesticulating, flinging my arms about my head. She stared blankly. Then we heard a disembodied voice from a far-off pool of light.

“AWWWK-w’d.”

Izzy and I exchanged uncomprehending glances. Again came the puzzling explanation from the voice far across the empty room: “AWWWK-w’d.” This time, as we made no answer, the owner of the voice stood up and sauntered all the way from his corner to ours, doling out a letter with each step, “A-W-K-W-A-R-D, awkward.” As he approached, I recognized the tall, nearly gaunt English exchange student. I had noticed him often, sitting alone in Commons, reading, smoking his pipe, or just observing.

“Awwk-werd, oh, we get it now,” we laughed, converting his beguiling musical enunciation to our own harsh Northeastern twang. But of course, though we now recognized the word, we three began to debate the meaning of ”awkward” and whether it meant the same as obstreperous. Keith explained, still in that appealing, mellow British accent, that brought his mouth into ever more enticing shapes, the use of “awkward” to describe a difficult noisy child, one who misbehaved, in fact, the way the Brits in the history book were misbehaving. This made some sense, but by then, we had launched into our first of many animated discussions about the differences between the English he was used to and “American,” as he called our tongue. So the word “obstreperous” and our debate over its meaning brought Keith and me together. If Izzy hadn’t asked her question, if we hadn’t been alone in the big room, or if other students had been between us, playing bridge and chatting noisily, Keith and I might never have spoken that night.

An hour later Keith smiled a shy smile, excused himself to return to his seat and pack his neglected books into his dark green cloth book bag like the ones we all carried in 1960. He pulled on his brown wool duffle coat and wound his long multicolored British college scarf round and round his neck. With a tentative backward look full into my eyes (not Izzy’s, I was sure) he slipped into the night, the swinging doors flapping shut behind him.

In less than two years, the words we exchanged were “I do’s.”

“Fatuity, maundering, infelicitous,” words I didn’t know kept cropping up in the books I read in bed beside Keith over the years of our marriage. “What does this word mean, honey?” His own book resting temporarily on his chest, his eyes rolled toward the ceiling. I swear the definitions must have been printed there in ink visible only to him.

“Fatuity: something quite stupid or silly,” he read slowly, before turning back to his own novel. At first, I looked them up, but then saw I didn’t need to. He had become my teacher.

One day years later, shortly after Keith’s death, I ran across a word I didn’t know. Out of habit, I started to turn to him for his help. In that moment, I fresh-grieved my loss.

These days, a different husband asks me, “What does this word mean?” I look up and smile and think of Keith.

“To the backyard,” I pointed by nodding in that direction as I balanced our iced teas on a tray.

“You mean the garden?” asked Keith, my new British boyfriend. I often needed to explain our American form of his language to him.

“We call it the yard here, Keith.”

He shuddered, “Yard is an ugly word for such a lovely place.”

Slowly, I explained, “Keith, here it’s the space behind the house, where kids play, women hang out the washing, and we’ll have our drinks.” I tried to be a patient teacher. I never imagined part of our new relationship would find me teaching English to an Englishman.

He curled his lip in disgust. “In England, yards are paved with tarmac, with a few dustbins in a corner. Yard is too ugly.” I liked the way he wrinkled his nose. My mind strayed from the lesson.

Dustbins, tarmac, where to begin? Keith and I often lapsed into our version of the Revolutionary War over linguistic differences.

Jello, jelly, and jam launched another skirmish. Brits eat jelly for dessert: here we put it on our toast. They’re happy to say jam when they’re spreading either jelly or preserves.

We had met in the fall of 1960 at Swarthmore College, Keith and I, at 21 and 20, he an exchange student from England, I a junior. In our first encounter, words and language formed the heart of the matter. One Saturday night, my friend Izzy and I sat studying European history together in Commons, a cavernous, high-ceilinged social center in Parrish Hall. By day, the high uncurtained Georgian windows filled the space with light. At night, the glass turned ink-black, and the room sank deep in gloom, except where a few floor lamps with their always cockeyed shades dotted the floor with narrow pools of dim light. The almost-fog of our cigarette smoke drifted through those pools.

Izzy looked up from her book. Annoyed by the need to interrupt her reading, she demanded, “What does this word mean, obstreperous?”

“What’s the context? Read me the sentence it’s in.”

Izzy read it, something about the conduct of British politicians in the House of Lords, debating hotly. Instead of supplying Izzy with another word, I began to act out the meaning, mouthing silent shouts, gesticulating, flinging my arms about my head. She stared blankly. Then we heard a disembodied voice from a far-off pool of light.

“AWWWK-w’d.”

Izzy and I exchanged uncomprehending glances. Again came the puzzling explanation from the voice far across the empty room: “AWWWK-w’d.” This time, as we made no answer, the owner of the voice stood up and sauntered all the way from his corner to ours, doling out a letter with each step, “A-W-K-W-A-R-D, awkward.” As he approached, I recognized the tall, nearly gaunt English exchange student. I had noticed him often, sitting alone in Commons, reading, smoking his pipe, or just observing.

“Awwk-werd, oh, we get it now,” we laughed, converting his beguiling musical enunciation to our own harsh Northeastern twang. But of course, though we now recognized the word, we three began to debate the meaning of ”awkward” and whether it meant the same as obstreperous. Keith explained, still in that appealing, mellow British accent, that brought his mouth into ever more enticing shapes, the use of “awkward” to describe a difficult noisy child, one who misbehaved, in fact, the way the Brits in the history book were misbehaving. This made some sense, but by then, we had launched into our first of many animated discussions about the differences between the English he was used to and “American,” as he called our tongue. So the word “obstreperous” and our debate over its meaning brought Keith and me together. If Izzy hadn’t asked her question, if we hadn’t been alone in the big room, or if other students had been between us, playing bridge and chatting noisily, Keith and I might never have spoken that night.

An hour later Keith smiled a shy smile, excused himself to return to his seat and pack his neglected books into his dark green cloth book bag like the ones we all carried in 1960. He pulled on his brown wool duffle coat and wound his long multicolored British college scarf round and round his neck. With a tentative backward look full into my eyes (not Izzy’s, I was sure) he slipped into the night, the swinging doors flapping shut behind him.

In less than two years, the words we exchanged were “I do’s.”

“Fatuity, maundering, infelicitous,” words I didn’t know kept cropping up in the books I read in bed beside Keith over the years of our marriage. “What does this word mean, honey?” His own book resting temporarily on his chest, his eyes rolled toward the ceiling. I swear the definitions must have been printed there in ink visible only to him.

“Fatuity: something quite stupid or silly,” he read slowly, before turning back to his own novel. At first, I looked them up, but then saw I didn’t need to. He had become my teacher.

One day years later, shortly after Keith’s death, I ran across a word I didn’t know. Out of habit, I started to turn to him for his help. In that moment, I fresh-grieved my loss.

These days, a different husband asks me, “What does this word mean?” I look up and smile and think of Keith.

"The Accidental Baptism" by Gwen Sibley

My friend Carolyn and I had spent that morning at the excavation site of Ephesus, Turkey, walking the dusty streets of a civilization that thrived in this coastal town thousands of years ago. We had collected water from the springs running under the house of the Virgin Mary, where it was said she lived after the crucifixion of her Son. After such a holy and historic morning, we returned to the port city where our cruise ship was docked to wander the streets looking for “Evil Eye” souvenirs.

It was while we were casually looking at Oriental rugs and talking with the English speaking owner of the store that he asked if we had ever had a Turkish bath. We met each other’s gaze with excitement and apprehension over the thought of the possibilities ahead. We had never turned down a chance to experience some crazy adventures in our years of travel together, such as when we climbed up the steep hill to the Acropolis in the searing summer heat just to sit on the steps of the Parthenon, almost collapsing on the way down, so why not go for it? But as I followed him through a maze of narrow, dirty alleyways, my Connecticut Yankee inner voice started whispering , “Are you crazy? No one knows you‘re doing this. The cruise ship could leave without you.”

But then the real reason why I was following this man flashed in front of me - a chance to reclaim myself after a bitter divorce a few years ago. I had gone from my parent’s house to my husband’s at the young age of twenty, without a day of living on my own, defining myself as a daughter and then a wife, always living in the shadows of someone else. After 23 years of living through and for another, I was just beginning to live for myself. Somehow I needed this bewildering escapade to validate myself in this very moment.

We reached the local bathhouse and our guide told the owner to take good care of us, leaving with a promise to return in two hours to bring us back to the ship. The spiral marble staircase in the center of the room brought us to a long narrow hallway with slatted wooden doors on either side. Behind each door was a tiny room where the owner told me to wrap the towel around me and meet him at the staircase. I could hardly see in that shadowy, incense filled room, but I undressed and wrapped the towel around my ample body, barely covering myself. Was I a sheep being led to slaughter?

Carolyn, the owner and I walked down more stairs until we discovered underground corridors lined with mosaic walls leading into a cavernous room. The owner left us and we were on our own. The room was filled with steam swirling out of a stone furnace in the center, rising up to a hole in the domed ceiling and spurting out into the sky. Men and women lined the walls, sitting on wooden benches, some with towels, some without. I was mesmerized. Within minutes my body was also drenched in sweat, the steam opening every pore of my skin and my mind as if I were being absorbed into the walls around me. Since other people were leaving the room, I forced myself to leave this hypnotic state and follow them. The corridor led to a bigger room, shaped exactly like the first, but in the center were two elevated marble tables. Along the walls were showers and small wooden stools. I raced for a shower and let the frigid water from the underground wells wash away my rivulets of sweat. I noticed the others were sitting on tiny stools until someone came to take them to one of the tables, so I squatted down upon my stool and waited. The wet towel still clung to my body, like some remnant of my former life. I still couldn’t let go of it. Suddenly a man offered his hand to lead me to the table. This must be the masseuse I thought, with visions of gentle Swedish massages I had experienced floating in my head.

Was I in for a surprise. With that first dowsing of water as the towel was whisked away, I knew I would remember this adventure forever. Every loofah scrubbed inch of my body tingled with delight in shedding my old layers of the past. As I looked up, slivers of light squeezed through the scattered openings of the ancient domed ceiling, luring my naked body to fly to the blue and white patchwork of the sky. I tried to focus on the pulsating canopy of light beams while I fought to hold myself onto the cold, wet marble table beneath me. Had I become a mystical offering to the Gods?

It didn’t matter that I was a plump, middle aged, nude, white American woman surrounded by mostly young, thin, dark, Turkish men in a bathhouse somewhere in Turkey, I felt free and open as I hadn’t ever felt since my divorce. I knew deep within that the Gods had accepted my offering and had awakened my soul. I had been baptized by the waters of Ephesus into a new and exciting world.

It was while we were casually looking at Oriental rugs and talking with the English speaking owner of the store that he asked if we had ever had a Turkish bath. We met each other’s gaze with excitement and apprehension over the thought of the possibilities ahead. We had never turned down a chance to experience some crazy adventures in our years of travel together, such as when we climbed up the steep hill to the Acropolis in the searing summer heat just to sit on the steps of the Parthenon, almost collapsing on the way down, so why not go for it? But as I followed him through a maze of narrow, dirty alleyways, my Connecticut Yankee inner voice started whispering , “Are you crazy? No one knows you‘re doing this. The cruise ship could leave without you.”

But then the real reason why I was following this man flashed in front of me - a chance to reclaim myself after a bitter divorce a few years ago. I had gone from my parent’s house to my husband’s at the young age of twenty, without a day of living on my own, defining myself as a daughter and then a wife, always living in the shadows of someone else. After 23 years of living through and for another, I was just beginning to live for myself. Somehow I needed this bewildering escapade to validate myself in this very moment.

We reached the local bathhouse and our guide told the owner to take good care of us, leaving with a promise to return in two hours to bring us back to the ship. The spiral marble staircase in the center of the room brought us to a long narrow hallway with slatted wooden doors on either side. Behind each door was a tiny room where the owner told me to wrap the towel around me and meet him at the staircase. I could hardly see in that shadowy, incense filled room, but I undressed and wrapped the towel around my ample body, barely covering myself. Was I a sheep being led to slaughter?